The remarkable resilience of radio

Joey Fisher demonstrates that radio isn’t giving up yet

I’m Still Standing

“You had your time, you had the power / You’ve yet to have your finest hour / Radio (radio)” so sang Freddie Mercury in 1984, a tribute and call to arms for the under-siege medium. Then and ever since, commentators have been predicting the demise of radio. Such doomsaying, however, has proved greatly exaggerated and radio has demonstrated a remarkable resilience, continuing to thrive despite the rise of television, the internet, and digital music.

In recent times, the explosion in podcast popularity is the latest development to have been touted as a radio killer. However, as with all the previous challenges radio has emerged relatively unscathed. Whilst podcasts are now a cultural mainstay, they still represent a niche interest compared to radio (with stalling growth in reach indicating this is unlikely to change) and podcast consumption has been shown to be more of a weekly habit than the integral part of daily life that characterises radio. Radio has thus remained strong, and audio as a whole has blossomed into a rich landscape, with the advent of newer media offering consumers greater listening choice than ever before.

Even the global pandemic could do little to dampen listenership, with radio avoiding the large consumption declines experienced by other legacy media, and (as seen above) still reaching 88% of the adult population every week. Radio’s enduring appeal is partly due to the ‘sense of community’ it can provide, and which other forms of audio have been unable to replicate.[1]

However, the landscape is set to change yet again, and radio faces a critical juncture with the dual spectres of streaming competition and distribution disruption looming.

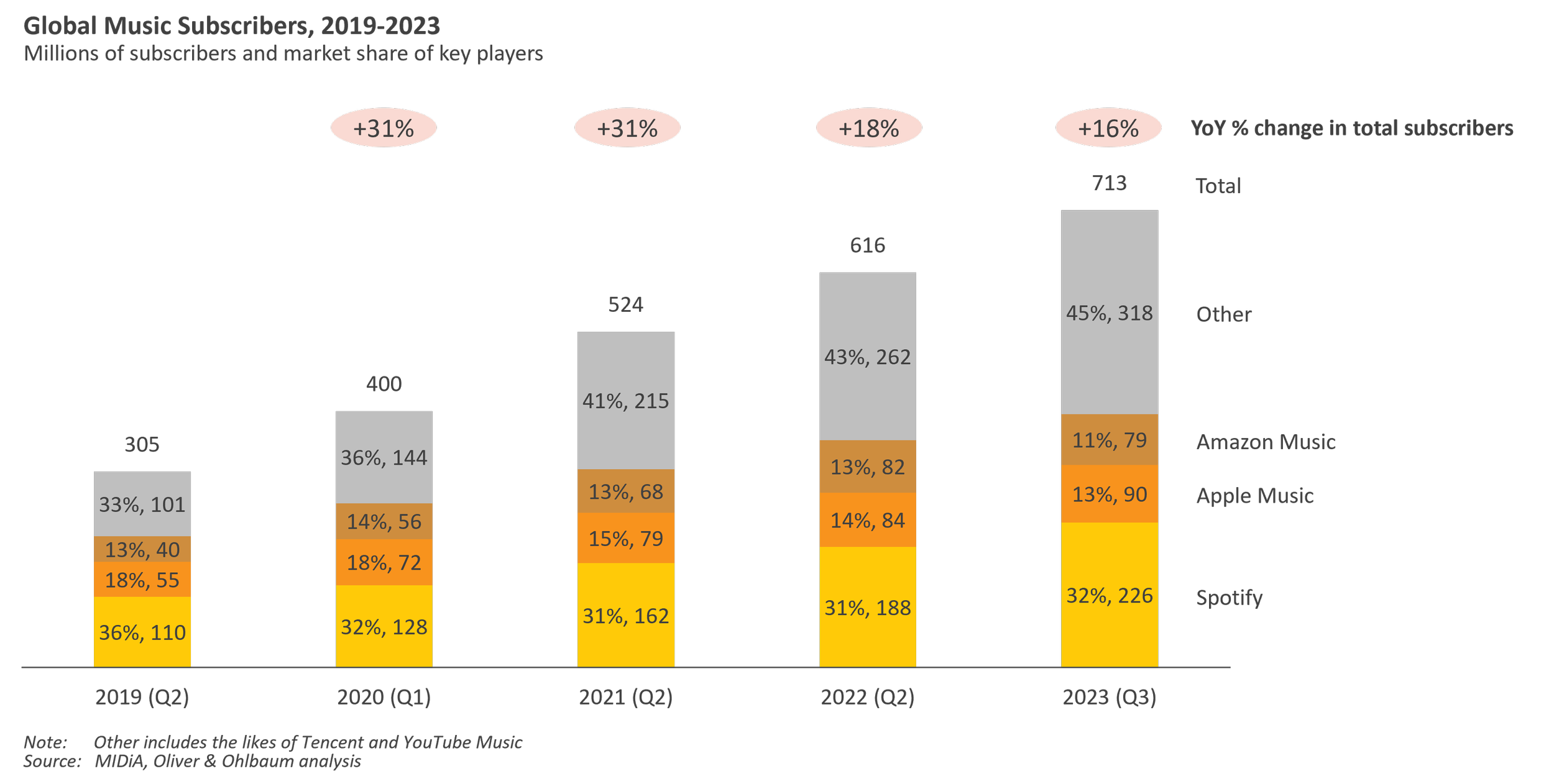

Stuck in the Middle with You

The next major threat to radio will likely come from music streaming platforms. For a number of years now, global giants Spotify, Amazon Music, and Apple Music have been waging an expensive war for domination of the audio streaming market. Whilst Spotify has established itself as the leading player, it appears a deadlock is being reached – Amazon Music has recently lost subscribers, Apple’s growth has all but stalled, and Spotify will soon feel the bite of the slowdown in total market growth – and it is immensely hard for any player to win subscribers off a rival. This market share stalemate stems from the homogeneity of their offerings: when the music is the same across platforms, and the price points are similar, users have little incentive to switch. Spotify's hefty investment in podcasts (now being rethought), Amazon’s focus on audiobooks (now being replicated by Spotify), and Apple's attempts to lock users into its ecosystem (now being challenged in the EU courts) have not significantly shifted market dynamics. The reality is that without substantial differentiators, such as exclusive content from major labels or artists, there's little room for these services to outmanoeuvre each other.[2]

Thieves in the Temple

Whilst the likes of Spotify may have been content in the past to leave radio alone, stalling growth and market share in music streaming and podcasts will likely force their hand making them compete more directly with traditional audio broadcasters; as seen in the UK, radio accounts for a huge 71% of listening time compared to streaming/podcast’s paltry 20%, so the logical growth area is in stealing share of audio from radio.

We have already seen the first steps from Spotify here, including scaled up advertising capabilities and the ‘DJ’ feature. If Spotify were to launch full-on live radio stations, then traditional players may find themselves squeezed out. The ‘live’ bit is key here, to compete with radio effectively these stations would need to fulfil the same sense of community and companionship, with everyone listening to the same music and the same presenters at the same time. Without this, the likes of Spotify DJ are just gloried shuffle functions.

As well as defending against the next salvos from the music streamers, radio is also having to contend with a changing distribution landscape. Currently, 28% of radio listening is still via AM/FM with these frequencies not long for this world; AM is already being phased out and whilst FM’s future is secured until 2030, aging infrastructure means it is likely broadcasting will cease soon after this date.[3]

A further 42.7% of radio listening is via DAB, but the future of this technology is also in doubt. The fate of DAB is entwined with that of DTT (digital terrestrial television) which, as calls for more spectrum to be given over to mobile data purposes grow, faces a very uncertain future – whether DTT continues post 2034 is an open question currently under review by Ofcom.[4]

So radio must look to transition its consumers to online listening – but carefully, as this path is full of its own snares and pitfalls. When it comes to online radio listening the smart speaker is king, accounting for 57.4% share (rising to 61.2% when just considering commercial radio listening) and growing, and the most popular smart speakers are made by radio’s audio rivals.[5] As radio grows more reliant on these smart devices, broadcasters may find their listening share siphoned off by the makers and gatekeepers of these devices as consumers find themselves pushed towards major streaming platforms which have been frictionlessly integrated.[6]

A similar story is at play for in-car. At 25% of total radio listening, in-car is hugely significant and this listening is increasingly online as consumption shifts towards connected smartphones and integrated infotainment systems – putting radio's presence in vehicles at risk.[7] It has been forecast that by 2035, 90% of households with cars will have access to a connected car.[8] In the same way that Amazon and Google will have the power to influence what we listen to over smart speakers, Apple and Google (through Android) are growing in power as gatekeepers of new in-car listening habits/technology and future UIs for in-car entertainment may only include radio options as an afterthought.

Come Together

Yet all is not lost for radio. The key to its survival and continued relevance may lie in collaboration. Just as traditional broadcasters have formed partnerships in the video-on-demand (VOD) sector, radio needs to adapt by creating a unified digital platform which can defend against radio-esque offerings from global digital players, can help transition consumers to online listening, and can offer a frictionless smart speaker or in-car experience. Currently, the fragmented landscape (switching between BBC Sounds, Global Player, soon-to-be-launched Rayo, etc.) makes online radio listening unattractive to casual listeners without a specific station in mind as well as to those listeners who like to flick between different stations, and makes the likes of Spotify seem much more attractive as a one-stop shop. The fragmented landscape also means that individual players have little power to demand a seat at the table for developing the future of in-car, whereas a unified voice might. Aggregated solutions do exist (e.g. Radioplayer), but these are underdeveloped and underinvested; in large part as each radio player wants to own the radio ecosystem rather than collaborate.[9]

Future Nostalgia

So what does this all mean for audio? Most likely there will be no outright winner (a good, safe conclusion), and the rich audio landscape will continue to offer consumers choice. Radio’s share of the market after the dust settles though will depend on how aggressively music streamers come after radio listenership, and how quick radio broadcasters are to present a unified front. Hopefully Freddie’s immortal words will continue to ring true: “Radio, someone still loves you.”

Notes:

[1] See Radiocentre’s Generation Audio analysis on need states for an in depth discussion of this

[2] Any major exclusivity play seems highly unlikely – both from the potential risk to artist exposure and from a cost to platforms perspective. Universal’s recent schism with TikTok has thrown the reality of this harshly into light

[3] RAJAR Q4 2023

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ofcom’s ‘Audio listening in the UK 2024’ report found that only 24% of smart speaker users had ever changed the default settings to a preferred provider of music

[7] RAJAR Q4 2023

[8] Mediatique, Ownership and use of audio-enabled devices in 2035

[9] Commercial radio and the BBC have in the past held negotiations for carriage on BBC Sounds, but recently these have broken down (see here)